Water is one of the primary molecules of life, which is why the majority of our bodies are composed of it. As a child, I struggled to comprehend this—shouldn’t we be relatively fluid then? I don’t think I ever found a satisfactory answer, nor did I truly seek one until I learned about the underlying physiological structure of organisms. Water is stored within cells or flows in extracellular fluids, while our organs and tissues maintain a semi-rigid form thanks to our skeletons. Water is also constantly moving throughout our bodies; it leaves us as we sweat, breathe, or excrete—so it must be replenished. This is why we drink, and why the sensation of thirst is so crucial. Quenching thirst not only deeply satisfies our senses but also keeps us alive. But where does this feeling come from? One might wonder: is it simply because our mouths feel dry? No. The craving for water is shaped by far more complex factors. Our brains have a thirst center where protein sensors measure the levels of molecules like salt or glucose in the blood. When our organs crave water, this need manifests in the blood, and chemical signals are sent to the brain to trigger the feeling of thirst. In animals, this sensor is known as TMEM63B.

Organisms are approximately 70% water. In humans, this level is estimated to be 60%. If we need it so badly, it’s because life depends on it. When we drink water, it directly enters the bloodstream, distributing moisture throughout the body—for example, helping cells perform daily tasks, transporting or dissolving nutrients, or carrying waste products out of the body. Specialized pores allow water molecules to move in and out of cells. These are called aquaporins, present across all domains of life, even in viruses. However, aquaporins are merely channels that allow water molecules to pass from one side of a membrane to the other. They are crucial for regulating water homeostasis within cells but are not responsible for generating the sensation of thirst.

What makes us crave water? It’s one of those intangible things in biology. We all know what it means and how it feels, yet it’s hard to put into words—except for the adjective “thirsty.” Animals instinctively know they must find water when they feel thirsty, and they will seek out a drop of dew, a freshwater lake, or a kitchen faucet. It all relates to an organism’s ability to perceive its internal state—such as water levels. This is the fascinating field of interoception, where our bodies tell us their needs by providing sensations—like thirst—prompting us to respond.

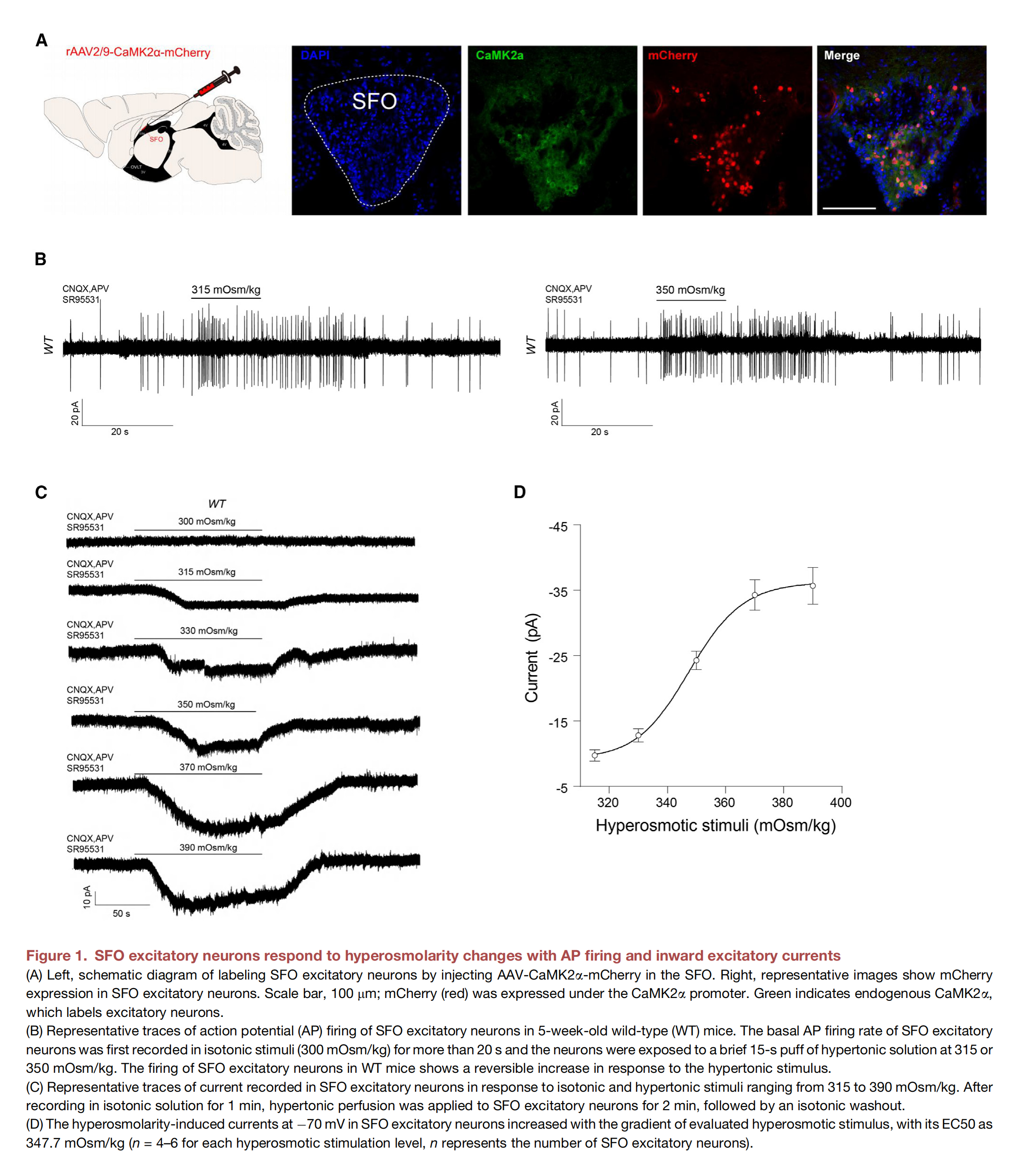

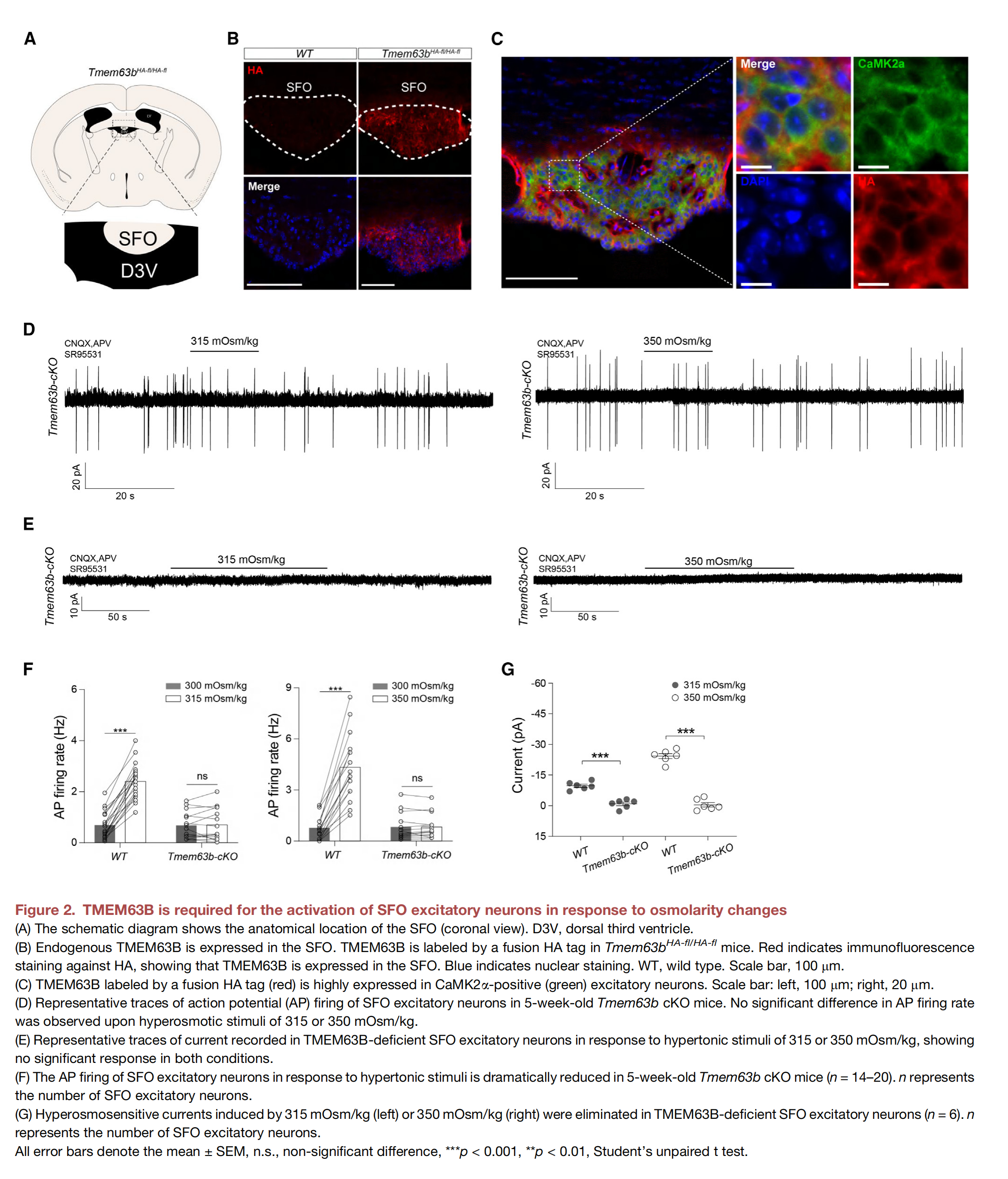

Scientists have long known that a part of our brain called the lamina terminalis is responsible for perceiving thirst, so much so that it is also referred to as the thirst center. Within the lamina terminalis lies the subfornical organ, or SFO for short. Through the (thirst) neurons that make up the blood-brain barrier, the SFO detects changes in blood osmolality—i.e., when the levels of solutes (such as salt or glucose) in the blood are too high. This occurs when water in the blood is absorbed by organs in need. What scientists couldn’t understand was how the SFO measures water deficiency, and how this information is interpreted and transmitted to the brain. The answer lies in mechanosensitive ion channels, also known as mechanical sensors. Mechanical sensors detect changes in mechanical forces, such as pressure or solute concentration, and open to allow ions to flow through. This ion flow ultimately converts the initial mechanical stimulus into an electrical or chemical signal that is transmitted to the brain. The existence of mechanical sensors was proposed by German-British biophysicist Bernard Katz in the 1950s. Twenty-five years later, Hungarian-American biophysicist Georg von Békésy suggested that certain mechanoreceptors must be able to perceive different tones in the ear. Finally, in the late 1980s, the existence of mechanosensitive ion channels in bacteria was conclusively proven.

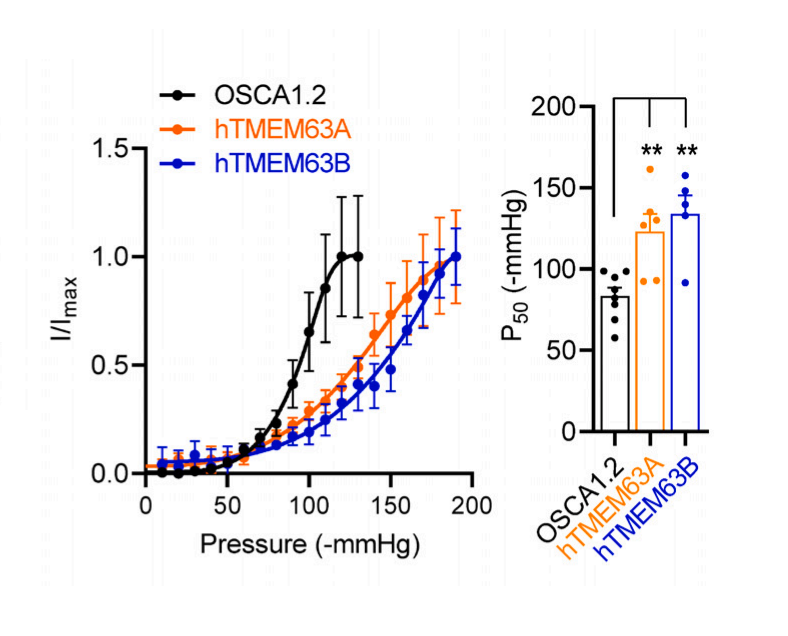

Mechanical sensors exist across all domains of life, in various tissues, and respond to a range of mechanical forces. The proteins present in the SFO were only identified recently, even though they belong to the largest family of mechanical sensors: transmembrane protein 63, or TMEM63 for short. The mechanosensitive ion channels of the TMEM63 family are conserved from plants (where they are called OSCAs) to animals and consist of three members: TMEM63A, B, and C. TMEM63B is highly expressed in SFO neurons and senses blood hyperosmolality. In other words, TMEM63B measures the phenomenon where the concentration of particles like salt or glucose is abnormally high due to water deficiency. This is converted into a chemical signal that is transmitted to the brain and translated into “thirst”.

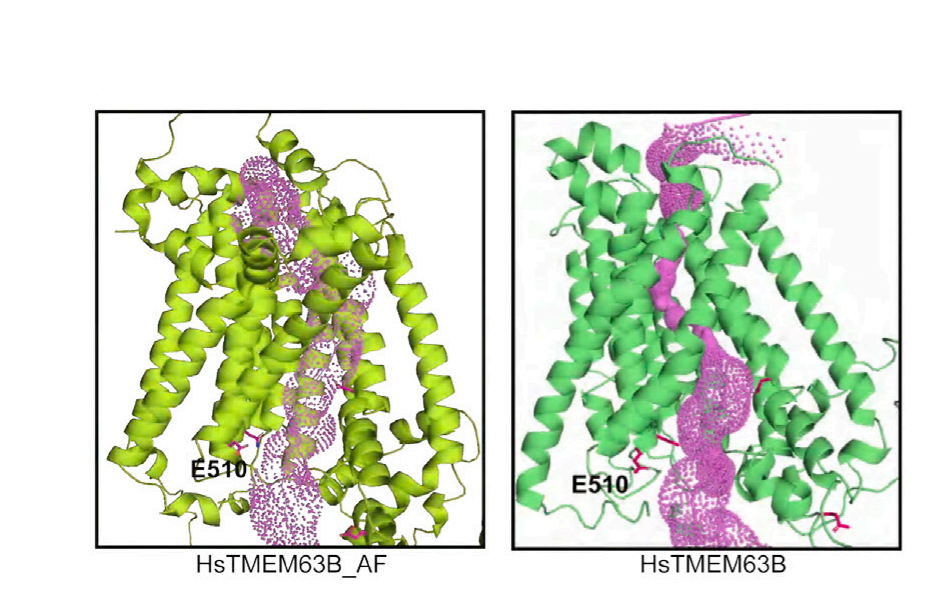

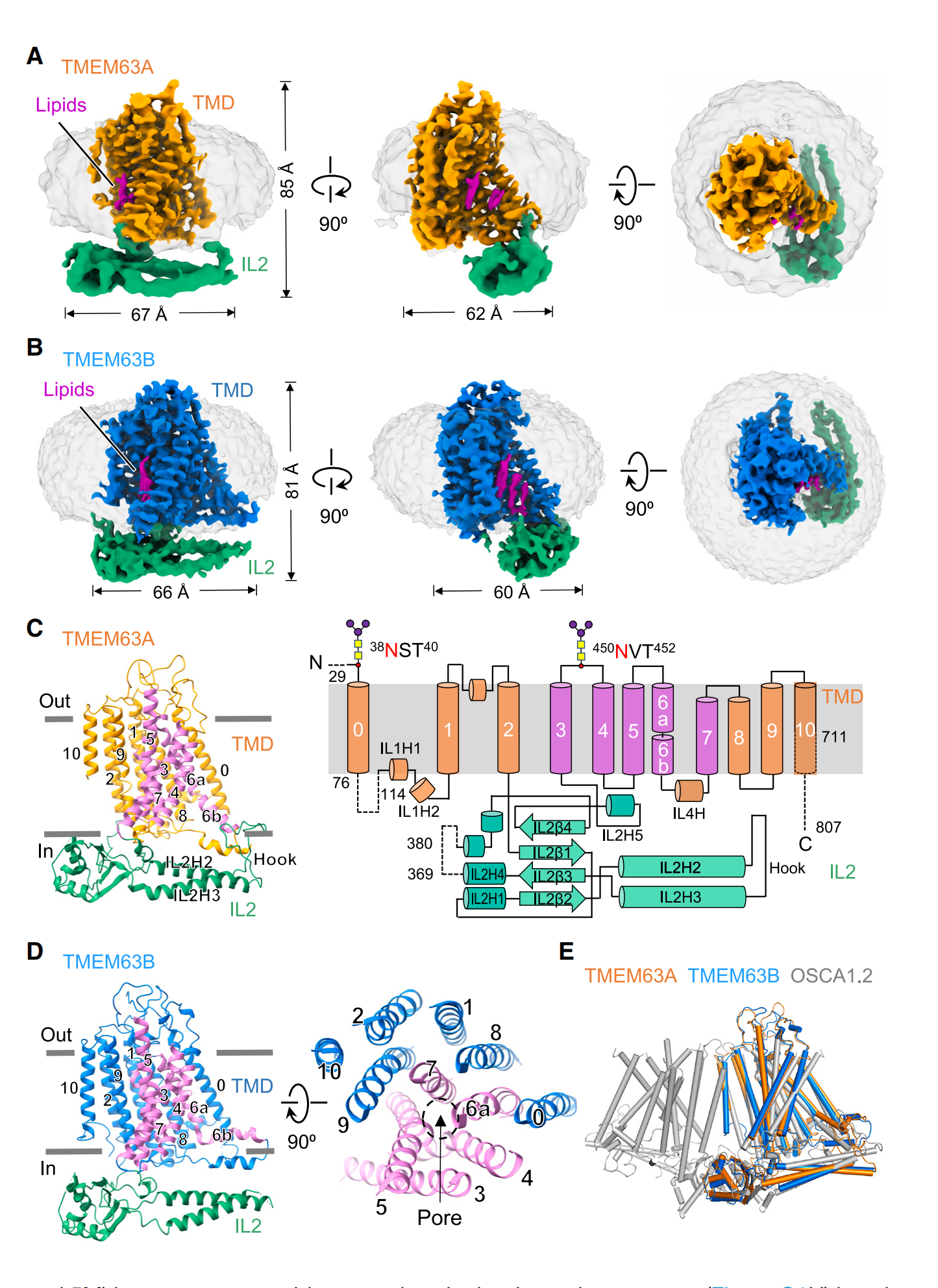

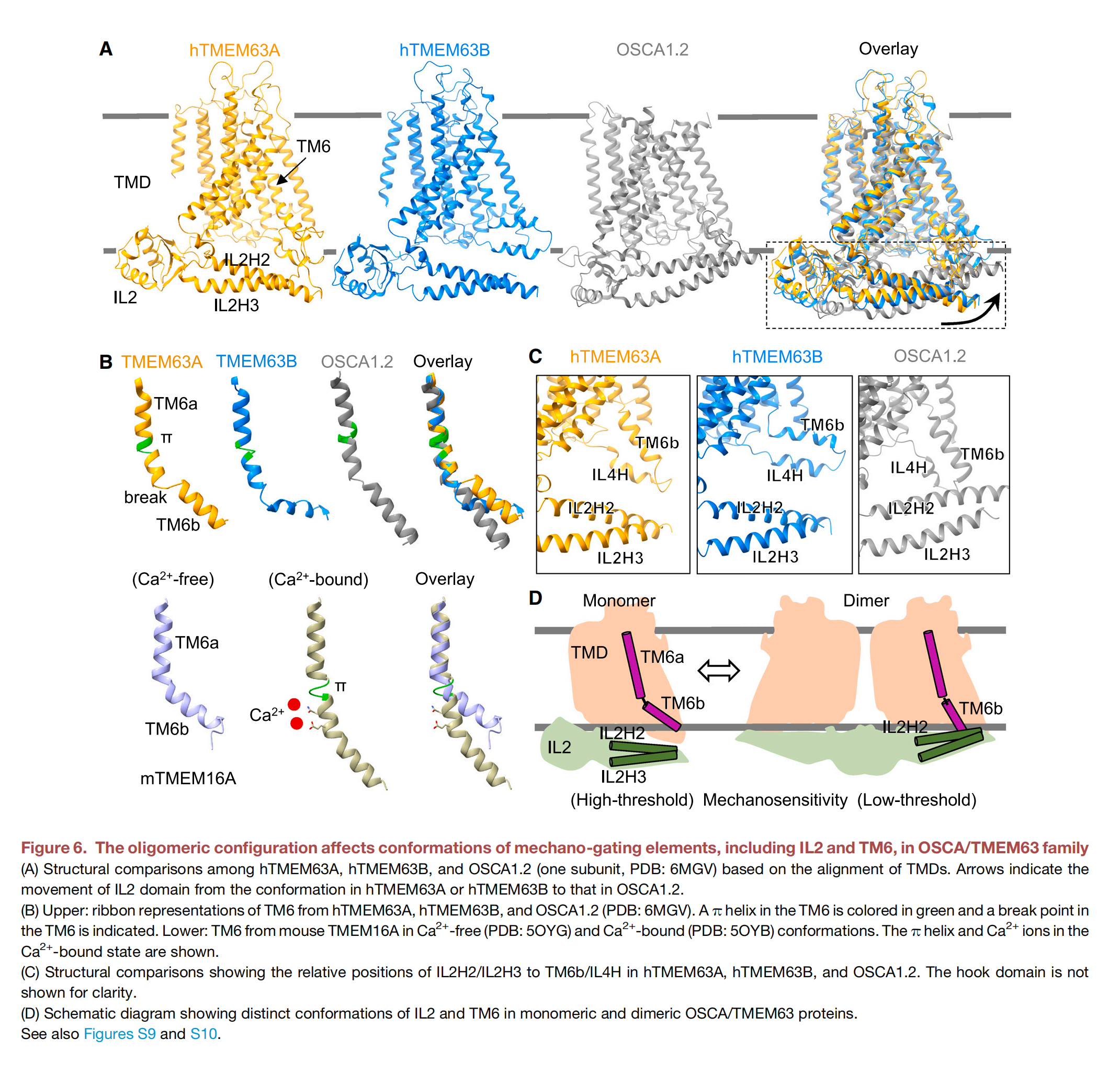

As a monomer, TMEM63B has 11 transmembrane helices that form the actual ion pore, an N-terminal domain folded into a hairpin on the outside of the channel, and a structure called IL2 that runs parallel to the inside of the channel. One end of IL2 forms a hook that extends into the membrane—suggesting it can sense membrane tension. Although not yet confirmed, the cavity formed by the transmembrane portion of TMEM63B may be used to deposit lipids. Lipids are crucial for regulating mechanosensitive ion channels, so this makes sense. Interestingly, the plant version of TMEM63, OSCA, functions as a dimer, even though each monomer forms a pore. Scientists propose that IL2 may be involved in forming monomers or dimers, especially since switching from one form to the other appears to affect mechanosensitivity—not by influencing pore conductivity, but by altering how long the pore remains open.

Have you ever wondered why everyone seems to carry a water bottle everywhere these days? People didn’t consume less water in the past, but this trend reflects our recognition of just how vital water is to our health—and for good reason. A lack of TMEM63 leads to impaired water homeostasis in the body, resulting in high blood pressure and kidney disease, as well as brain dysfunction such as intellectual disability and motor or visual impairments. No matter how we look at it, life is a matter of balance—or in biological terms, homeostasis. Homeostasis is essential for life, which is why we, like tightrope walkers, and all living organisms, spend a great deal of time and energy striving to maintain stability.

References

1. Zou W., Deng S., Chen X. et al.

TMEM63B functions as a mammalian hyperosmolar sensor for thirst

Neuron 113:1430-1445(2025)

PMID:40107268

2. Zheng W., Rawson S., Shen Z. et al.

TMEM63 proteins function as monomeric high-threshold mechanosensitive ion channels

Neuron 111:3195-3210(2023)

PMID:37543036