Why cAMP?

In the field of life sciences, there is a molecule widely regarded as the “gold standard” of signal transduction research—cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Since its Nobel Prize–level discovery in 1957, this tiny “second messenger,” composed of only 10 carbon atoms, has been found to regulate countless biological processes ranging from blood glucose control and neural activity to cancer progression. Today, let’s lift the veil and explore its mysteries.

Where Does cAMP Come From?

The Classical “Production Line”

cAMP is generated from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) under the catalysis of adenylyl cyclase (AC). This reaction consumes ATP and removes two phosphate groups, forming the unique cyclic structure of cAMP. Mammals possess 10 AC isoforms: 9 transmembrane ACs (tmAC1–9) and 1 soluble AC (sAC or AC10)

The Mysterious “Export Pathway”

Intracellular cAMP can be actively “pumped” out of the cell by ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABCC/MRP). Once outside the cell, it is converted into adenosine by ecto-phosphodiesterases (ecto-PDEs) and CD73. This non-classical pathway plays a critical role in diseases such as asthma and COPD.

How Does cAMP Work? — Compartmentalized Signaling

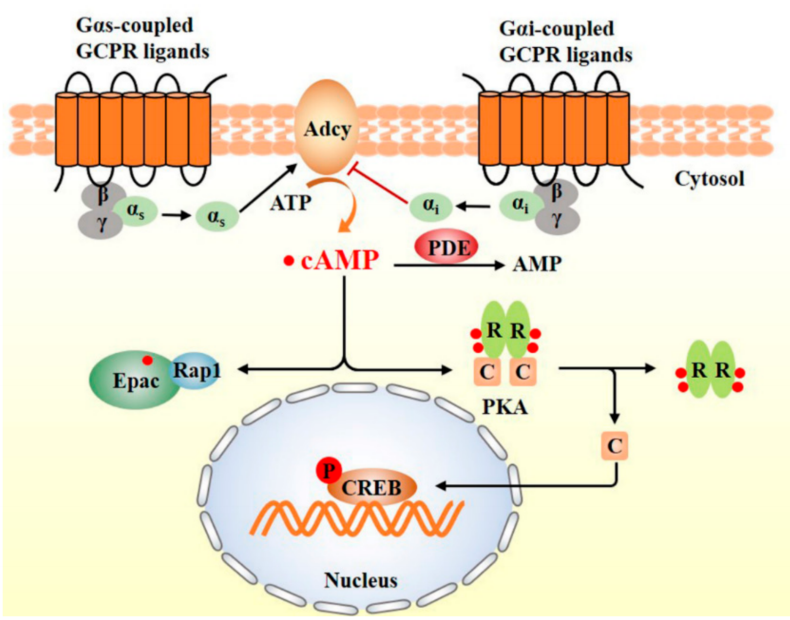

PKA Pathway: cAMP binds to the regulatory subunits of protein kinase A (PKA), releasing catalytic subunits that phosphorylate substrates such as CREB, thereby regulating gene expression.

Epac Pathway: cAMP directly activates Epac proteins, modulating small G proteins like Rap1.

CNGC Regulation: cAMP directly activates cyclic nucleotide–gated channels.

Rather than diffusing randomly within the cell, cAMP signaling is spatially and temporally controlled through A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs), forming discrete “signaling microdomains.” This explains how the same molecule can exert vastly different functions in different cell types.

Schematic diagram of the cAMP signaling pathway [Wang Y, et al.]

The “Superpowers” of cAMP

cAMP acts like a “supreme commander” inside the cell, with its core powers manifested across four dimensions:

Metabolic Regulation: It maintains systemic glucose homeostasis—promoting insulin and glucagon secretion in the pancreas, driving gluconeogenesis in the liver, and mediating insulin-independent glucose uptake and lipolysis in muscle and adipose tissue.

Memory Formation: In the hippocampus, cAMP shapes long-term memory through the PKA–CREB pathway.

Immune Modulation: It behaves as a “double agent”—at high concentrations suppressing excessive inflammation to protect tissues, while at low concentrations promoting immune cell recruitment.

Neural Regeneration: After nerve injury, cAMP acts as a “regeneration trigger,” activating regeneration-associated genes to promote axonal repair and functional recovery.

The Love–Hate Relationship Between cAMP and Disease

1. As a Therapeutic Target

The therapeutic potential of the cAMP pathway spans metabolism, respiratory diseases, neurology, and oncology.

Diabetes: GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide) enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by activating the cAMP/PKA pathway in pancreatic β-cells. Natural compounds such as resveratrol and curcumin improve hepatic and muscular glucose metabolism by inhibiting PDE4B.

Respiratory Diseases: While classic β₂-agonists relax bronchial smooth muscle via cAMP, aberrant activation of the cAMP-to-adenosine conversion pathway in airway epithelial cells can exacerbate asthma, suggesting combined targeting of CD73 or cAMP efflux mechanisms to improve efficacy.

Neurological Disorders: PACAP-induced activation of cAMP/CREB shows neuroprotection in models of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. Selective AC1 inhibitors (e.g., NB001, ST034307) can alleviate neuropathic pain without opioid-like side effects.

Cancer: Particularly striking, inhibitors targeting PDE8/11 activators or PRKACA fusion proteins are under development. The major challenge lies in precisely intervening in driver mutations such as GNAS or PDE11A without disrupting normal physiology. This “same pathway, different diseases” phenomenon is driving a new era of genotype-based precision medicine centered on cAMP signaling.

2. Disease-Causing Mutations

Multiple mutations in cAMP pathway genes can drive tumorigenesis:

How to Capture This “Messenger”? — Detection Methods

Concentration Measurement:

ELISA (Most Recommended): Simple operation, no expensive equipment required; suitable for serum, plasma, cell culture supernatants, and tissue homogenates.

Reed Biotech cAMP ELISA Kit (Cat. No. RE10092) — Four Core Advantages:

pg-level sensitivity: Detection limit of 92.5 pg/mL

Broad sample compatibility: Serum, plasma, cell lysates, tissue homogenates, and more

Rapid assay: Complete detection in just 1.5 hours

No acetylation required: No derivatization, low error, high reproducibility (CV < 5%)

Radioimmunoassay: High sensitivity but requires radioactive isotope facilities

Mass Spectrometry: LC–MS/MS for precise quantification; expensive instruments and complex operation

Genetic Testing: NGS screening of GNAS, PDE, PRKAR1A mutations

Phosphorylation Analysis: Western blot detection of CREB and phosphorylated PKA substrates

Live-Cell Imaging: Real-time monitoring of cAMP dynamics using FRET probes

Mass Spectrometry: LC–MS/MS quantification of cAMP and adenosine

References

1. Pacini ESA, Satori NA, Jackson EK, Godinho RO. Extracellular cAMP-Adenosine Pathway Signaling: A Potential Therapeutic Target in Chronic Inflammatory Airway Diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:866097. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.866097

2. Tomczak J, Kapsa A, Boczek T. Adenylyl Cyclases as Therapeutic Targets in Neuroregeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(13):6081.. doi:10.3390/ijms26136081

3. Wang Y, Liu Q, Kang SG, Huang K, Tong T. Dietary Bioactive Ingredients Modulating the cAMP Signaling in Diabetes Treatment. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3038. doi:10.3390/nu13093038

4. Bolger GB. The cAMP-signaling cancers: Clinically-divergent disorders with a common central pathway. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1024423. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.1024423